Introduction

A protein is a long string of amino acids that is folded into a specific 3-D conformation. Because a protein’s shape determines the way it functions, knowing its surface topography is an important part of understanding the protein. Very often it is an essential piece of knowledge for drug development.

The determination of a protein’s 3-D structure is often very difficult. The problem arises from the fact that there are loops, folds, and twists on the surface of the protein. These features distort the linear sequence of amino acids in such a way that residues appearing next to each other on the surface of the protein are in fact not close to each other in its linear sequence.

Traditional methods of protein structure determination such as X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance are not always possible or convenient. A computational method of 3-D structure determination would allow for the surface structure of a protein to be efficiently modeled. We are developing one such computational method to use the information provided by phage display.

Phage Display and Preliminary Analysis

Phage display is a technique used to obtain the amino acid sequence of an antibody binding site on a protein, known as the antibody epitope (Scott and Smith, 1990). An antibody that is known to bind to a particular protein is exposed to a large library of random peptides that are carried by bacteriophage (Burritt et al., 1996). After a series of amplifications and selections, a sample of the phage is sequenced. From the phage DNA sequence, the sequence of amino acids on a phage can be determined. This residue sequence is highly similar to the antibody epitope found on a protein. This sequence of residues can then be compared with the amino acid sequence of a protein to determine the conformation of the binding site.

Because an antibody binding site on a protein is a 3-D surface formed by individual amino acid residues, it often does not resemble any linear sequence found in that protein’s polypeptide sequence. Thus, it is believed that computational methods will be extremely valuable in the identification and mapping of antibody epitopes. A program called FINDMAP (Mumey et al., 2003) compares the sequences of numerous probes, which are highly conserved, to the sequence of the probes’ target protein. A scoring system was developed based on protein-protein interactions. The scoring system is organized into a matrix that is used by the branch and bound algorithm. Using the algorithm, FINDMAP is able to construct possible arrangements of surface amino acids at the probes’ binding site.

Filtering Alignments

In order to fully realize the information provided by FINDMAP, an additional program needed to be developed to select the most probable sequence of amino acids for each probe. FINDMAP’s output consists of a list of possible alignments for each probe. According to the algorithm that FINDMAP uses, each of these alignments is equally probable. The Alignment Filter then determines which of these alignments are the must mutually compatible. Thus, a list of just one alignment per probe, is the output from the Alignment Filter. This collection of binding site sequences can then be graphed to visualize a single probable consensus antibody epitope.

The Alignment Filter works in three main stages. First, the alignments from the FINDMAP output file are compared to each other and the results of the comparisons are arranged in a matrix. Next, the scores in the matrix are used in a modified branch and bound algorithm to predict the most likely alignment for each probe. Finally, these alignments are output to a file and a histogram is drawn representing the binding site.

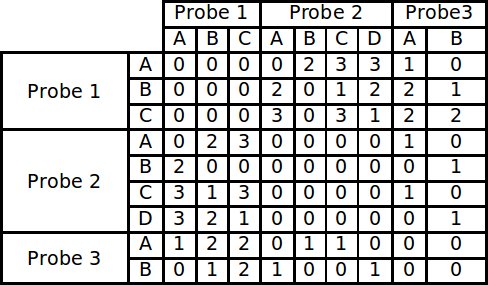

The first section of the program that runs is a routine that builds a large matrix. This matrix is built by comparing all the alignments of each probe to each other and scoring each conflict that exists. In order to account for the possibility that not all the probes bind in the same position, the residues are first broken into small contiguous sequences, called runs, found in the main sequence. These runs fall into two categories, increasing and decreasing, according to the direction in which the peptide bound during phage display. Each increasing run in a probe is compared to all of the decreasing runs in another probe. Therefore every time a “matching” run is found, a conflict exists in actuality. The alignments are not only compared in the default direction in which they were fed into the program, but their reversed sequence is also compared. Comparing the reversed sequence accounts for the directionality problem encountered by traditional alignment methods. Each conflict score is stored in a matrix to be used as input for the modified branch and bound algorithm.

Example of a conflict matrix constructed from 3 probes each with 4 runs.

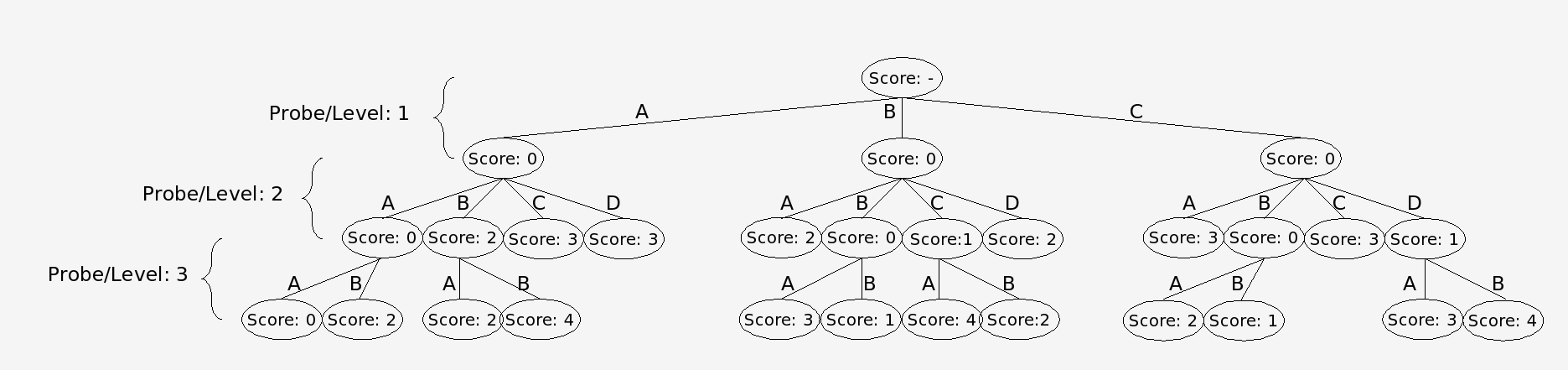

In the branch and bound algorithm a tree of possible alignment solutions for each probe is created. This algorithm works by summing up all the conflict scores in a particular solution. The best solution will be the one with the lowest score. The difficulty with finding the best possible solution arises because the optimum solution for the data set is not known. One way to solve this problem is to simply follow every branch to a terminal node and complete the tree. This approach is undesirable, however, because it puts a huge demand on computing resources. Instead nodes in which descendants cannot produce a optimal solution are not expanded and are “pruned from the tree.” It is known that a descendant cannot be an optimal solution if its parent node has already surpassed the maximum score that can be produced by an alternate branch (Land and Doing, 1960). In our modified algorithm, however, the nodes are arranged into dynamically maintained Priority Queues, according to the node’s score. Each node’s score is determined by the sum of the number of conflicts between all the alignments that make up the path to that node. Only the best nodes found at any level are expanded, allowing for a statistically accurate solution using fewer computational resources.

Nodes are trims via the branch and bound algorithm using the conflict matrix as input.

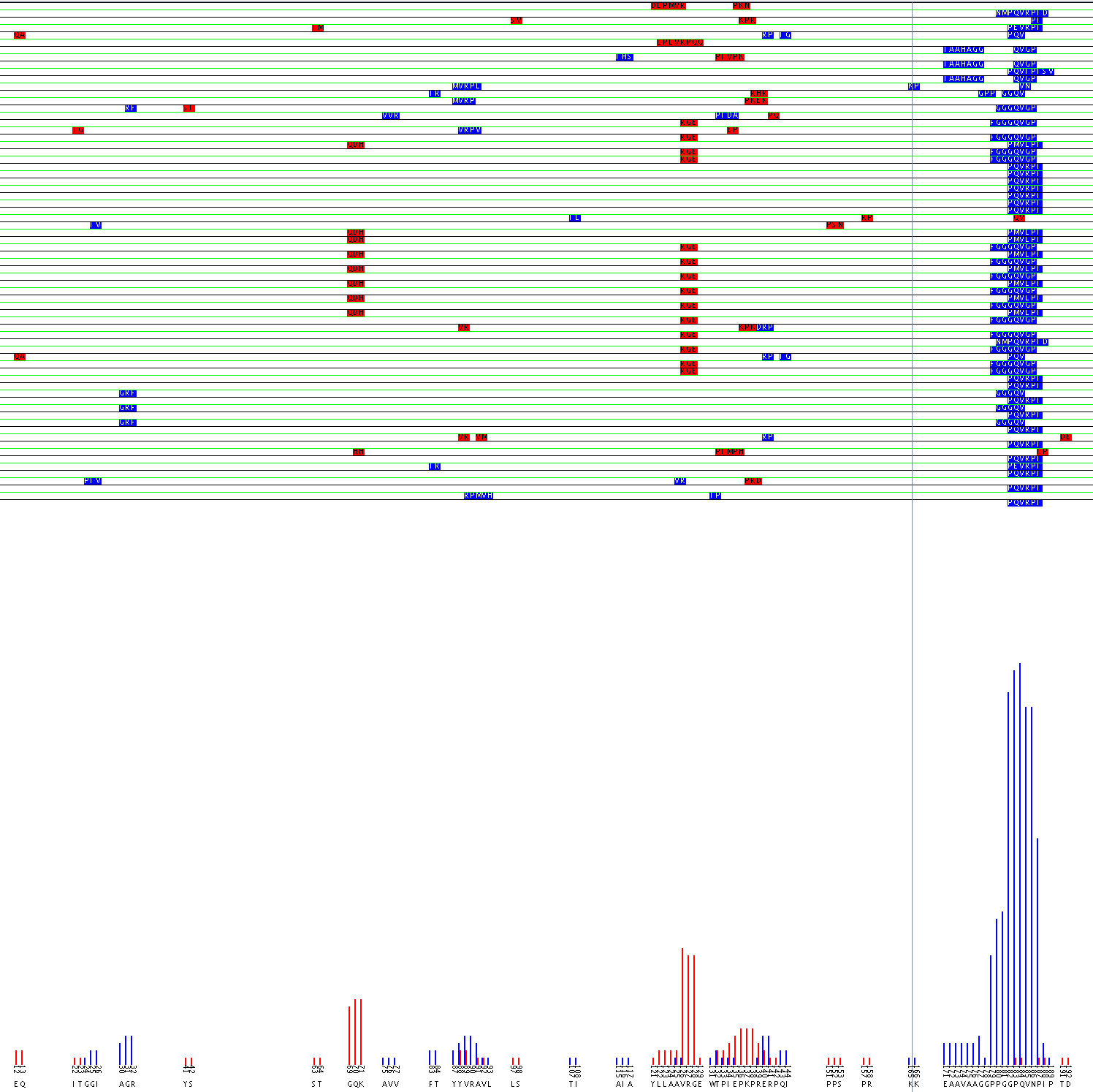

The output from the algorithm is then stored in a text file and is also shown in a graphical format. The graph shows the relative orientation of each of the alignment runs. From the graph the user can infer the possible surface structure and a consensus sequence of the antibody epitope even if it is discontinuous.

Analysis of the discontinuous epitope of flavocytochrome b 558

Alignment of Flavocytochome b 558 44.1 epitope using the aligment filter

The value of the Alignment Filter lies in the fact that it can identify possible discontinuous epitopes. Experiments can then be designed to confirm the epitope suggested. A possible epitope for monoclonal antibody 44.1 was identified on flavocytochrome b 558 (Burritt et al., 1998). The sequence PQVRPI was strongly returned during phage display. That sequence matches well with 183PQVNPI188, however because residue 186, asparagine, does not match with the arginine found in the probes’ sequence it is likely that mAb 44.1 has a complex epitope. Burritt suggested that the arginine may be mapped to the region 29TAGRF33. However, computational analysis of the data using the alignment filter predicts that the arginine in the epitope may be mapped to either the 88YVRAV92 or 125AVRG128 region as seen in the the graphical output of the alignment filter.

Future Program Improvements

One major change that has the potential to increase the accuracy of the Alignment Filter is to take into consideration similarities between sequences in the scoring scheme. In the current version only conflicts are scored. However, similarities in sequences are most likely significant and should therefore be weighted when filtering alignments. This revised scoring routine would be more complete and would likely be more accurate.

The second improvement needed to maximize the power of this suite of epitope mapping programs is the ability for them to be run on large scale data sets. To efficiently work on a large scale the programs need to be synchronized so that they can process the data with a minimal amount of human direction. In addition to synchronization, the output data needs to be encoded with a tag so it can be stored and located easily for future reference.

With these modifications, computational analysis of phage display data promises to be a powerful tool in protein structure determination.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Nathanial T. Ohler who helped extensively with the development of this program and Brendan M. Mumey for supervising the process. I would also like to thank Edward A. Dratz, Algirdas J. Jesaitis, and Thomas E. Angel for providing data and insight during the testing of this program. The project described was supported by NIH Grant Number P20 RR16455-05 from the INBRE-BRIN Program of the National Center for Research Resources.

References

J.B. Burritt, C.W.Bond, K.W.Doss, and A.J.Jesaitis. Filamentous phage display of oligopeptide libraries. Anal. Biochem. 238:1-13, 1996.

J.B. Burritt, S.C.Busse, D.Gizachew, D.W.Siemsen, M.T.Quinn, C.W.Bond, E.A.Dratz, and A.J.Jesaitis. Antibody imprint of a membrane protein surface. Phagocyte flavocytochrome b. J. Biol. Chem. 273:24847-24852, 1998.

A. H. Land and A. G. Doig, An Automatic Method for Solving Discrete Programming Problems. Econometrica. Vol.28, pp. 497-520, 1960.

B.M. Mumey, B.W.Bailey, B.Kirkpatrick, A.J.Jesaitis, T.Angel, and E.A.Dratz. A new method for mapping discontinuous antibody epitopes to reveal structural features of proteins. J. Comput. Biol. 10:555-567, 2003.

J.K. Scott and G.P.Smith. Searching for peptide ligands with an epitope library. Science 249:386-390, 1990. PAGE 7